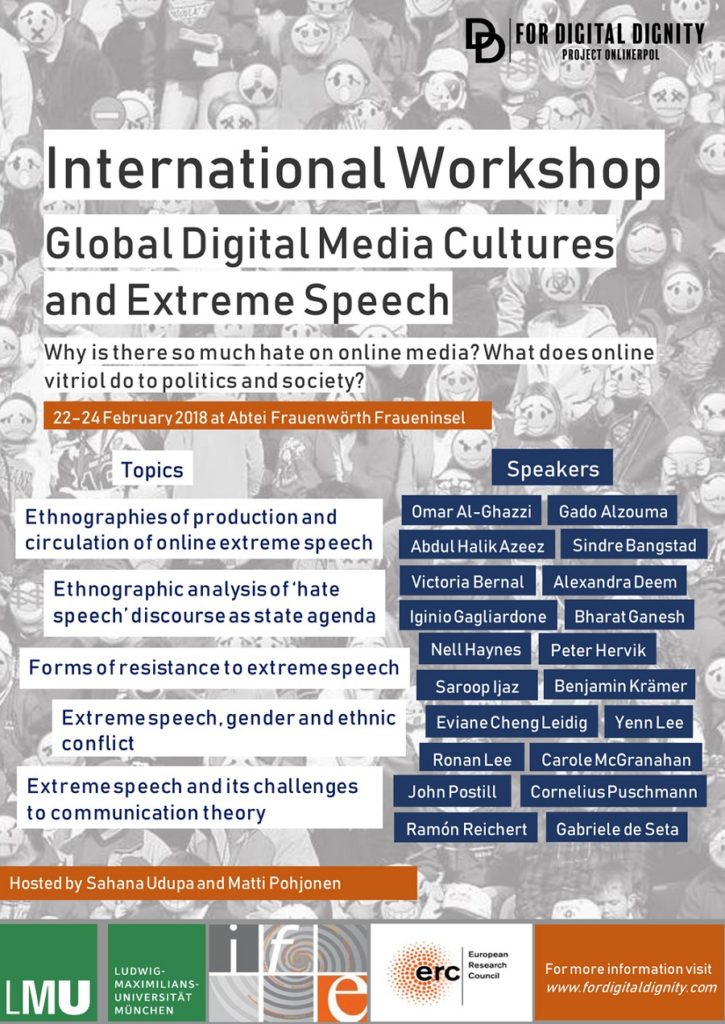

GLOBAL DIGITAL MEDIA CULTURES AND EXTREME SPEECH

International Workshop at LMU Munich

Convened by

Sahana Udupa, LMU Munich & MattiPohjonen, Africa Voices Foundation

22 – 24 February 2018

Recent political upheavals in Europe and the US have once again highlighted the paradoxical nature of contemporary digital communication. The celebratory discourse of digital technologies’ potential for openness and democracy is now eclipsed by the “dark side” of new media as a platform for promoting hate speech, fake news, terrorism, misogyny and intergroup conflict. Researchers are confronted with a new lexicon of communicative tactics: ecosystems of fake news; disinformation campaigns; coordinated troll attacks; and targeted hacks aimed at influencing elections. Calls to monitor, legislate and remove hateful and violent online speech have also reinvigorated older legal, political and philosophical debates on the boundaries of accepted civility and legitimate forms of political communication. The negative forms of online speech, it is widely argued, threaten the taken-for-granted freedoms commonly associated with digital media cultures across the world and bringing about what some critics have called a “post-truth” society.

Despite this heightened sense of urgency, these concerns are, however, by no means new or limited to the Western world. A cursory glance of many examples from the “global South” reveals a long-standing anxiety about the dangers of unbridled speech in situations where it can provoke ethnic and religious conflict, mass violence and social unrest. In Ethiopia, for example, following a series of violent protests and killings, the government has declared a state of emergency and made political commenting on Facebook illegal under the pretext of preserving peace. In India, social media is replete with acrimonious abusive exchange in political debates. Legal stipulations to prevent hate speech on grounds of religious harmony and national security are routinely invoked to regulate online media in India, Pakistan, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. In Myanmar, social media has been used widely by Buddhist groups to ignite violence against its Muslim minority. In all the cases, digital media have also evolved into vibrant forums for political participation and counter-speech.

The aim of the Global Digital Media Cultures and Extreme Speech workshop is to examine these paradoxes of contemporary digital communication from a critical-comparative perspective rooted in ethnography. By defining online vitriol as “extreme speech”, we depart from the dominant legal definitions of “hate speech” and narrowly constructed terrorism talk. As a form of digital culture, “extreme speech” pushes the boundaries of legitimate speech along the twin axes of truth-falsity and civility-incivility, raising critical questions about some of the taken-for-granted assumptions of communication and political participation. “Extreme speech” serves to reinforce differences and hatred between groups on grounds of religion, race, political ideology and gender, often with the overt intent to intimidate and agitate target groups and individuals. Yet, its ambivalent nature in certain contexts could also provoke challenges to established hegemony. “Extreme speech” thus foregrounds an approach to digital cultures as forms of situated practice (i.e. what people do that is related to media within specific cultural contexts) in order to avoid predetermining the effects of online volatile speech as vilifying, polarizing or lethal (Pohjonen and Udupa 2017).

Event Report on International Workshop: Global Digital Media Cultures and Extreme Speech

The International Workshop on Global Digital Media Cultures and Extreme Speech, convened by Sahana Udupa (LMU) and Matti Pohjonen (Africa Voices Foundation), brought together an inter-disciplinary group of researchers to understand and examine the multi-layered legal, political, and social complexities implicit within the paradoxes of global digital communications and extreme speech as a form of digital culture. Held between 22-24 February 2018 at the scenic island of Frauenchiemsee, the workshop explored how ethnographic sensibilities can contribute to the study and understanding of these digital social practices by problematising the assumed linearity between digital communication and political participation. The workshop built on the concept of “extreme speech” as an anthropological critique of the regulatory, legal discourse around “hate speech” (Pohjonen and Udupa, 2017). By developing a deeper appreciation of extreme speech as a spectrum of practices and the dynamic boundaries of legitimate speech through scholarship developed within both Global North and Global South contexts, it aimed to develop a critical-comparative understanding of extreme speech both as a phenomenon and a practice.

The workshop started with a session on Theories and Concepts with presentations by Iginio Gagliardone (University of the Witwatersrand) and Yenn Lee (SOAS). Iginio laid down the different typologies of dangerous speech (hate speech, dangerous speech, fear speech, violent extremist speech, incitement to violence, and microaggression) and spoke about the need to approach these issues by thinking about antagonism and/ or agonism as ways of becoming political or anti-political. Yenn’s research into (university) students’ online expression of complex political issues showed that people often have an intuitive understanding of hate speech i.e. ‘they know it when they see it’. However, there still remains the problem of framing who decides what is acceptable, when one intervenes, and how the mechanism actually works to change things. This session revealed a tension of thinking online politics via political theory and/ or anthropological concerns of life worlds, networks, technologies and practices.

The session on Theories and Concepts was followed by a session on Methods and Approaches where Peter Hervik (University of Copenhagen) underscored the need for empathy-driven field work with a person centric approach while Carole McGranahan (University of Colorado) highlighted the need to understand social media (esp. Twitter) as a public archive of the present, a space where lived life unfolds in a side-by-side way’, thereby presenting a new coevalness. This session saw engagement with the concept of ethnographic seduction or humanisation of the subject whose views/ actions/ ideologies the researcher finds repelling. However, it also raised questions about critical perspectives and the role of ethics therein.

Following the sessions on Theories and Concepts and Methods and Approaches, the workshop moved on to Pushing the Boundaries of Accepted Speech: Gossip, Lying, Humour, and Rewriting History.

This session foregrounded the need for extreme speech to be thoroughly contextualised in local and translocal dynamics as well as the need to take infrastructure and affordances seriously within intermedia and transmedia research that follows or traces tropes across physical spaces and communicative contexts. In his paper on digitally mediated contention in China, Gabriele de Seta (Academia Sinica) argued that using the term ‘problematic practices’ could help to flesh out differences with relation to specific tropes surrounding civility and incivility. Tracing the metaphor of the ‘Garbage dump of history’ Omar Al-Ghazzi (LSE), in his work on the temporal reach of extreme speech, argued how certain speech acts and tropes can be appropriated in a given social moment by different groups across the political spectrum. In her research on racialised jokes on Bolivian immigrants on Northern Chilean social media, Nell Haynes (Northwestern University) demonstrates the mainstreaming of extreme speech by sharing of humourous memes, even by those who would not engage in extreme speech otherwise.

The session on Misuses and Violence saw presentations on the ramifications of extreme speech in legal contexts and within political and ethnic violence across Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Eritrea. Saroop Ijaz (Human Rights Watch, Pakistan) explained how Pakistan’s cybercrime law of 2015 is used against activists and common people in order to crush dissident voices. Ronan Lee (Deakin University) engaged with the question what happens when hate speech comes from the government in his research on the Rakhine State and Rohingya minorities in Myanmar. Abdul-Halik Azeez’s (University of Granada) critical discourse analysis of online construction of national identity in post-war Sri Lanka showed how within a Sinhala Buddhist supremacy Tamil and Muslim minorities are often labelled as one, with negative stereotyping and expletives. While sub-groups that call for unity and reconciliation also exist. In her research on post-war negotiation of online identities between supporters of two major political groups in post-independence Eritrea, Victoria Bernal (University of California, Irvine) showed that discussions centred on identity politics and legitimacy where criticism was often equated with being a traitor. It also highlighted the role of authority that moderators exercise on such platforms where in most other cases they prefer to remain anonymous.

Given the contemporary explosion of online content related to Race, Populism and Right-Wing Extremism, the session was split into two in order to encompass the wide ranging scholarship on topic. In the first session Alexandra Deem (University of Amsterdam) used the conceptual framework of contagion and digital traces to understand the logics of collective and connective action when tracing ‘whiteness’ through the popular hashtag #whitegenocide. In her research on ideological and transnational connections between Hindutva and the populist radical right, Eviane Cheng Leidig (Centre for Research in Extremism, University of Oslo) argued that Indian Hindus in diaspora act as nodes for transnational ideological linkages, translating the fusion of Hindutva and radical right discourse to not only further populist radical right narratives but to help it adapt towards new boundaries of inclusion/ exclusion. Sindre Bangstad (KIFO) showed how public figures like Hege Storhaug act as polarisation entrepreneurs and brokers translating anti-Muslim and anti-Islamic tropes into Norwegian contexts thereby mainstreaming far-right and Islamophobic ideologies.

In the second session, Benjamin Kramer (LMU) analysed the basis for grievance and social structures within ‘Losers of Modernisation’ economic precarisation and global competition as a reaction to cultural change. Bharath Ganesh (Oxford Internet Institute) posited the concept of ‘white thymos’ to explain the digital circuits and affective network of audiences of extreme speech in the UK and the US, where ‘white thymos’ is the term for anger, pride, and responses to perceived past injustices. Cornelius Puschman (Alexander von Humboldt Institut für Internet und Gesellschaft) demonstrated how different populist groups in Europe are connected with overlapping audiences, though analysis of social media of Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against Islamisation of the West) and AfD (Alternative for Germany). Matti Pohjonen (Africa Voices Foundation) introduced the concept and methodology of the ‘anthropology of complex systems’ though his study on a comparative approach to social media hate speech with a focus on Finland and drawing from his previous work in Ethiopia.

The discussions threw up new challenges about how the key themes (materiality of new media, digital traces, effects, pleasure, fun, platform specificities), that emerged during the workshop, can be taken towards an analytical abstraction. It also underscored the need to discover creative responses to hate speech and how de-escalation takes place while highlighting the importance of moving closer to the phenomenon by historicising it and understanding it as a situated practice. Conceptualising hate speech as something that happens on the margins and isolating it from broader developments in society makes it difficult to see the wider changes happening therein. Understanding extreme speech as intentional performances to stretch boundaries where cultural variations often dissolve such boundaries leads one to a key question, whether extreme speech can be separated from the moral gaze and normative stance.

Report by Anulekha Nandi.